How Hiroo Onoda Survived Isolation for 29 Years

A park on the Philippine island of Lubang preserves the legacy of a Japanese holdout who survived on bananas and meat for nearly three decades.

It’s been a grand total of 8 days since we officially started isolating in Portland, Oregon. In that time, I have growled at no fewer than two children, paced the entirety of my adopted home in a fitful attempt to quiet the howling fantods, and slammed drawers in protest to the clean dishes that are stacking up next to the kitchen sink. That’s right: I’m angry about the dishes being clean. (They’re wet. They’re there.) Eight days for my isolation to fester into open rebellion.

I am most certainly not the only person feeling the isolation right now. Friends are stranded alone in their apartments, travel is widely condemned, and everywhere I look I see people threading electronic lifelines through internet portals like Zoom and FaceTime and Instagram, the most disciplined approach to finding connection in a world where almost everything else is suspended. Even outdoor rec is largely off-limits, and rightly so.

Sheesh. Three weeks ago, I was gleefully planning a climbing trip to Las Vegas. Now I'm duty-bound to quarantine myself to my sister's bungalow. What the hell, man?

About 75 years ago, the world was embroiled in the last, most widely spread global outbreak, World War II. Hiroo Onoda was a Japanese ex-pat working for the Tajima Yoko trading company in Hankow, China—known these days as Wuhan—when he was called up by the Imperial Japanese Army to serve in the Philippines. An intelligence officer trained by the government in guerrilla warfare, he was deployed to the garrison at Lubang, a small and forgettable island in the Verde Island Passage between the strategically important islands of Mindoro and Luzon. His orders, handed down by his commanding officer, Major Takahashi, were simple:

You are absolutely forbidden to die by your own hand. It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens, we'll come back for you. Until then, so long as you have one soldier, you are to continue to lead him. You may have to live on coconuts. If that's the case, live on coconuts! Under no circumstances are you [to] give up your life voluntarily.

Onoda and his command were bound by orders to avoid the enemy and survive at all costs, traveling only to secure the absolute survival essentials until the enemy was triumphantly defeated.

Sound familiar?

The parallels to our modern crisis are clear enough. Among many, a duty- and honor-bound devotion the cause of survival, even if alone. During the war, ichioku gyokusai, which translates to “one hundred million souls dying for honor," was a common phrase in Japan.

There are few figures as honorable and beleaguered as Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda. By the time he was deployed on December 17, 1944, American forces had already landed on Mindoro, securing the island in 3 days. About 3 weeks later, the Allies bypassed Lubang entirely and landed on the main island of Luzon on January 9, 1945. Within a few days, 175,000 American soldiers had crossed the Verde Island Passage en route to an assault on Manila, essentially stranding Onoda and his company on Lubang. Onado’s war was essentially over before he saw his first combat.

When a reconnaissance force landed on Lubang in early 1945, Onoda retreated into the island's mountainous interior to resist and wait out Japanese reinforcements. But by September, Mamoru Shigemitsu signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, ending the Japanese-American conflict and thus World War II, while Onoda and his company, unaware, had dug into mountainous terrain where they would fight as guerrillas, alone—for the next 29 years.

How the hell does this happen? For starters, Japanese military forces at the outset of World War II were distributed as widely as the islands in the South Pacific. As they pushed into Japanese territory, it was common for American forces to ignore remote Japanese-controlled islands entirely, opting to sever their communications and supply lines rather than fight the Japanese down to the last man. Inspired Japanese holdouts sometimes persisted for years after the war was over.

Onoda was perhaps the most inspired holdout of them all, and he proved himself to be a highly resilient outdoorsman. He and his company subsisted on whatever they could find. He learned how to weave waraji, traditional Japanese sandals. He stayed in motion, carrying everything he could in a 45-pound pack on a circuit of the island that he could travel about four times during the dry season, which lasted 8 months. He moved between camps every 3 to 5 days, managing the threat of discovery and the availability of food, most of which was stolen. “In hunting for food, we aimed mainly at the islanders’ cows,” Onoda wrote in his memoir, No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War. Fighting malnourishment, he supplemented with the occasional wild game and bananas harvested from plantations.

“During the first year we slept crowded together in our little tent, even in the rainy season,” Onoda wrote. Being a mountainous, tropical island, it rained, a lot. “Often when the rain came down in buckets all night long, it did no good to stay huddled up in the tent. We still got soaked to the bone. Our skin would turn white, and we would shiver from the cold, even though it was summer. Often I felt like screaming out in protest.”

Although a highly capable commanding officer, there were still struggles within the group dynamic. He and his three remaining men fought often, sometimes over food, other times over enemy movements or desertion. Finally, one man deserted in September 1949. Another was shot and killed by a search party in 1954. Onoda lived out most of the rest of his isolation with just one other man, a loyal private named Kozuka who lived on until 1972.

But it was Onoda’s persistence through a wide variety of campaigns to convince him that the war was over, that he could come out of hiding, in which he truly showed his resolve. “After March [1946] there were more and more leaflets urging us to surrender,” wrote Onoda, "and from time to time we heard people calling to us in Japanese. Later on, the Japanese who had surrendered began leaving notes for us saying, ‘Nobody is searching for you now but Japanese. Come on out!’ But we could not believe that the war had really ended. We thought the enemy was simply forcing prisoners to go along with their trickery.”

Trickery.

Even the outside world seemed to lure Onoda with messages of peace. Lubang developed quickly in the post-war years, developing an electric grid sometime in the early 1950s. “Electric lights were shining in Tilik!” Onoda exclaimed, referring to a region of the island’s interior. “It had been six years since I had seen electric lights, but the sight of them did not make me the slightest bit homesick. That surprised even me. I had become so accustomed to having no lights at night that Tilik just looked like a different world from the one I was living in.”

Otherworldliness.

Meanwhile, out on the open ocean, Onoda could see that traditional sailing vessels were replaced by the tankers we’re more familiar with today. He saw a new lighthouse constructed on Cabra Island to the west of Lubang to help the tankers navigate, to which Onoda quipped: “The sight of something outside Lubang affected me not at all, and I wondered whether I had lost my ability to feel."

Numbness.

But Onoda's honor was most demonstrative in 1959, when the Japanese dispatched one of many search parties to Lubang best described in Onoda’s own heart-wrenching words:

We slipped up to the peak nearest the one we called Six Hundred. I did not know it then, but this was to be the last day of the search. From the top of Six Hundred came the sound of a loudspeaker saying, "Hiroo, come out. This is your brother Toshio. Kozuka’s brother Fukuji has come with me. This is our last day here. Please come out where we can see you.” The voice certainly sounded like Toshio’s, so I thought at first the enemy must be playing a record made by him. The more I listened, however, the less the voice sounded like a recording. I went a little closer so that I could hear better. […] I could not see the man’s face, but he was built like my brother, and his voice was identical. “That’s really something,” I thought. “They’ve found a Nisei or a prisoner who looks at a distance like my brother, and he’s learned to imitate my brother’s voice perfectly.” The man started to sing, “East wind blowing in the sky over the capital . . .” This was a well-known students’ song at the Tokyo First High School, which my brother had attended, and I knew he liked it. It started out as a fine performance, and I listened with interest. But gradually the voice grew strained and higher, and at the end it was completely off tune. I laughed to myself. The impersonator had not been able to keep it up, and his own voice had come through in the end. I found it very amusing, particularly so because at first he had nearly taken me in. Suddenly, it began to rain. A squall was rising. The man on the hill picked up something lying at his feet and started down the hill, his shoulders drooping. After I saw him safely out of sight, I slipped back into the jungle. When I returned to Japan, I learned that it had really been my brother.

Everything, including family, was part of an enemy ruse. “But time had stopped for us in 1944,” Onoda wrote. To Onoda, the outside world had become something to be weathered until, and only until, Japanese military forces returned to the Philippine Islands, victorious.

In a way, that’s what it finally took. In 1974, a college dropout named Norio Suzuki managed to find Onoda, who would only surrender if ordered by his commanding officer. Suzuki returned to Lubang with Major Taniguchi, who had since become a bookseller, and who disbanded Onoda from his military post on the spot.

“I was fortunate that I could devote myself to my duty in my young and vigorous years,” Onoda said in a New York Times report shortly after he emerged. Asked what had been on his mind all that time in the jungle, Onoda said, "Nothing but accomplishing my duty.”

Duty.

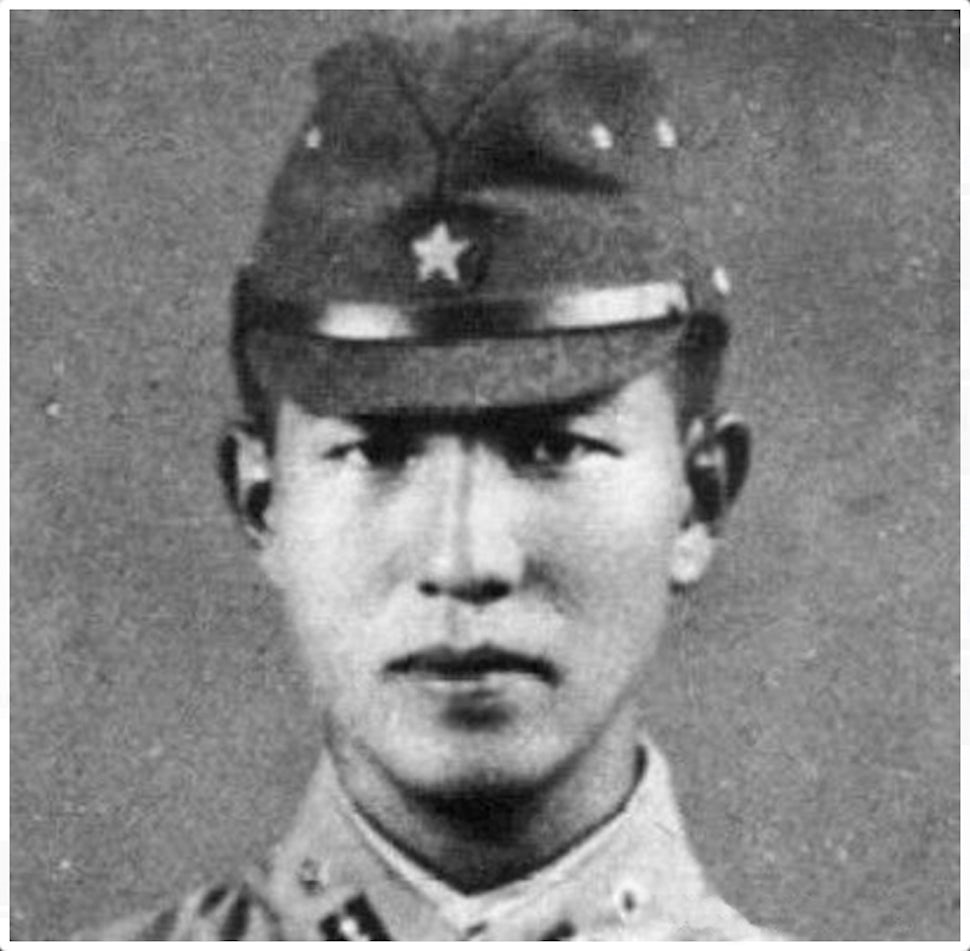

After emerging from Lubang, Onoda eventually established a wilderness survival school for youth, the Onoda Nature School. He died in 2014 at the age of 91. To commemorate his legacy, the trail and caves on the island of Lubang where Onoda hid from Allied forces were enshrined as a park, the Onoda Trail and Caves, in 2011. Photo of Hiroo Onoda courtesy of Segunda Guerra Mundial/Flickr.

We want to acknowledge and thank the past, present, and future generations of all Native Nations and Indigenous Peoples whose ancestral lands we travel, explore, and play on. Always practice Leave No Trace ethics on your adventures and follow local regulations. Please explore responsibly!

Do you love the outdoors?

Yep, us too. That's why we send you the best local adventures, stories, and expert advice, right to your inbox.